|

Manila is the capital of a country blessed by an economic resurgence -- and yet afflicted still by misery. Photograph: Virgile Simon Bertrand/Bloomberg Markets

|

Just after midnight one sultry Friday in August 1987, Manila became a battleground as rebel troops attempted a coup against Philippine President

Corazon Aquino. Two blocks from the besieged presidential palace, insurgents opened fire on a car carrying Aquino’s only son, a bespectacled and soft-spoken 27-year-old junior insurance executive nicknamed Noynoy.

Dec. 2 (Bloomberg) -- Timothy Riddell, the Singapore-based head of Asian global markets research at Australia & New Zealand Banking Group Ltd., talks about the region's economies and markets. He speaks with Mia Saini on Bloomberg Television's "First Up." (Source: Bloomberg)

President Benigno S. Aquino III

The leader of the Philippines, President Benigno S. Aquino III, has a strong economy to build on as he faces a new challenge: reconstructing a nation battered by Super Typhoon Haiyan. Photograph: Steve Tirona

In the Storm's Wake

A resident sells fruits and vegetables next to a public market destroyed by Typhoon Haiyan. Photograph: Ted Aljibe/AFP/Getty Images

Bonifacio Global City

Bonifacio Global City, a major new building development, rises on the edge of Manila. Photograph: Virgile Simon Bertrand/Bloomberg Markets

By the time soldiers still loyal to the president fought their way to the scene, three of Noynoy’s four bodyguards lay dead. Shot five times, the intended target improbably survived, albeit with a bullet in the neck that he still carries today, Bloomberg Markets magazine will report in its January issue.

“I’m living a second life,” says

Noynoy Aquino, now himself the president of this Southeast Asian nation of almost 100 million people. “I was saved for a certain purpose and will not squander that opportunity.”

So far, Benigno S. Aquino III -- his full name -- has largely proved true to his word and given the Philippines a second life of its own in the process. Since moving into an official residence known as the House of Dreams, following his election victory in June 2010, Aquino, 53, has overseen a national resurgence beyond the reveries of most investors.

Bankrupted in the 1980s by dictator

Ferdinand Marcos, the Philippines lagged far behind rival Asian economies, averaging just 3 percent annual growth from 1984 to 2009, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. Under Aquino, that figure has more than doubled. And in the first half of 2013, output surged at a 7.65 percent annual pace, surpassing that of China, the world’s fastest-growing major economy, before easing back to 7 percent in the third quarter.

Super Typhoon

In the aftermath of Super Typhoon Haiyan, Aquino must now try to sustain that growth while rebuilding whole swaths of his country and reinforcing its defenses against future, similar disasters. The tropical storm, which struck on Nov. 8, may have caused losses of as much as between $10 and $15 billion, according to early estimates.

Still, reconstruction is within Aquino’s reach, JPMorgan said in a November 22 report. The bank forecast that while the typhoon may cut full-year 2013 GDP growth to 6.9 percent from its earlier estimate of 7.1 percent, the nationwide impact won’t be long-lasting and the 2014 estimates should rise to 6 percent from 5.6 percent due to the boost from rebuilding.

The history of comparable catastrophes shows that reconstruction can be a boost for developing nations.

In 2012, Thailand’s economy rebounded 7.1 percent, following floods that swamped thousands of factories and a vast strip of agricultural land the previous year. In 2005, the Indonesian economy grew to 5.6 percent from 5 percent the year before, when a tsunami claimed about 200,000 lives and devastated Aceh province.

Best Performer

Investors in the Philippines weren’t unduly scared off by Haiyan, with the Philippines Stock Exchange Index falling 2.8 percent since Nov. 8 when Haiyan hit the Philippines.

From the time Aquino took office, the index has soared 86 percent, becoming the world’s best performer out of 45 emerging and developed markets tracked by MSCI indexes. The nation’s debt, meanwhile, has been raised to investment grade by Fitch Ratings, Moody’s Investors Service and Standard & Poor’s.

Now, investors are awaiting full-year GDP figures to see by how much the typhoon dented the country’s China-challenging growth rate.

Aquino has achieved this transformation by pruning a record $7 billion budget deficit in 2010 to $2.3 billion in the first nine months of 2013, declaring war on rampant corruption, announcing plans to more than double state spending on public works to $19 billion -- or about 5 percent of GDP -- by 2016, and exploiting Filipinos’ English-language skills to promote industries as diverse as casinos and call centers.

Filipinos Overseas

Foreign income from those call centers, together with remittances from 10.5 million Filipinos who work overseas, even helped Aquino defy the 2013 rout in other emerging markets -- especially those such as India with current-account deficits -- as investors anticipate an end to U.S. monetary easing.

The Philippines, by contrast, boasts a current-account surplus of more than 4 percent of GDP and should remain well placed to deal with the U.S. Federal Reserve’s eventual tapering, according to the International Monetary Fund.

That surplus has helped prop up the currency, the peso. Its 6.5 percent decline against the dollar in the 12 months ended on Dec. 3 is only a little more than half that of the Indian rupee. And although the stock market has fallen back from its May 15 record high, it was still up 9 percent during the same one-year period compared with less than 1 percent in the MSCI Emerging Markets Index.

Rolls-Royce

During that time frame, Philippine bonds have returned 8.7 percent, the best performance among 10 local-currency Asian bond markets tracked by

HSBC Holdings Plc.

Such is the wealth being generated in at least the upper echelons of Philippine society that Bayerische Motoren Werke AG in September opened its first Rolls-Royce showroom in Manila.

“The Philippines for decades was a lost country,” says

Ruchir Sharma, New York–based head of emerging markets at Morgan Stanley Investment Management who oversees $25 billion, including Philippine shares. “Now, it could end up being among the fastest growing in the world in 2013. It comes from having the right leader at the right time.”

Maintaining such investor enthusiasm is more problematic. The stock market surge since Aquino took office now makes the Philippines the world’s second most expensive emerging market after Mexico, with a 12-month forward price-earnings ratio of 16.9 compared with 7.8 for Chinese stocks listed in Hong Kong, according to data compiled by Bloomberg.

‘Too Expensive’

Investor

Mark Mobius says he’s not buying at those prices.

“It’s just too expensive,” says Singapore-based Mobius, who oversees $53 billion at San Mateo, California–based Templeton Emerging Markets Group. “There’s a shortage of good companies. They need more IPOs.”

That isn’t the only challenge facing the Philippines. The nation is locked in a territorial dispute with its giant neighbor, China, over the potentially oil-rich Spratly Islands in the South China Sea, while at home it is struggling to pacify a four-decade-old Muslim insurgency in southern Mindanao.

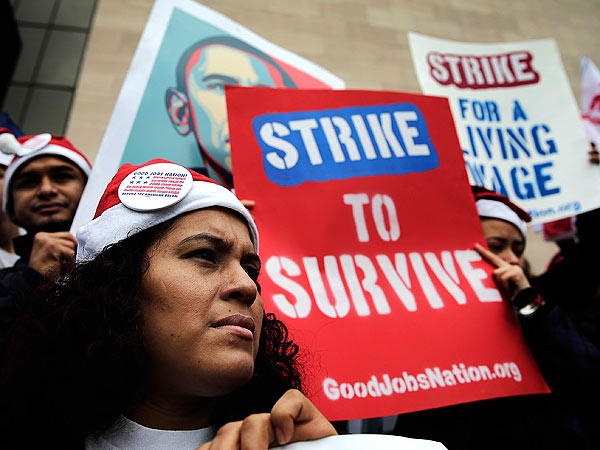

Even as the economy soars, almost 20 percent of the population continues to live on less than $1.20 a day -- the poorest in squalid slums or sometimes in cemeteries, where they squat in the family tombs of the wealthy.

Calamitous Storm

More than 10 million people were affected by November’s typhoon. An unemployment rate of 7.3 percent is Asia’s second highest, after India. Foreign direct investment is the lowest in Southeast Asia -- just $2.8 billion in 2012 compared with $8.6 billion for Thailand. The $250 billion economy remains dependent on the $21 billion sent home annually by Filipinos working overseas.

While Haiyan was an exceptionally calamitous storm, natural disasters are far from rare in the Philippines, costing the nation an average of $1.6 billion a year, according to the Asian Development Bank.

Aquino’s battle against graft perhaps best reflects the enormity of his task. During his 2010 election campaign, he argued that it was impossible to beat poverty without first eradicating corruption.

Soon after being elected, he set about doing that by sacking Chief Justice

Renato Corona for failing to disclose his assets. Aquino also arrested

Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo, his immediate predecessor, on corruption charges that have yet to come to court. Both Corona and Macapagal-Arroyo deny wrongdoing.

Crusading Commissioner

Aquino also hired a crusading female tax commissioner,

Kim Henares, 53, who has so incensed some of her targets that she has taken to carrying a pistol for self-defense.

Aquino’s efforts appear to have borne some fruit. His country’s ranking in Transparency International’s 2013 Corruption Perceptions Index, announced on Dec. 3, improved 11 places to 94th out of 177 countries.

Still, in recent months, these victories have been clouded by the disclosure that pork-barreling politicians have been misusing a $568 million poverty-reduction fund that they have been allowed to access at their own discretion. The scandal has wounded Aquino: His net satisfaction rating fell 15 points to plus-49 in September, according to polling firm Social Weather Stations.

For Aquino himself, time is running short. He is constitutionally barred from running for a second six-year term, and June will mark his fourth anniversary in office.

“You will quickly see him moving toward lame-duck status,” says

Frederic Neumann, Hong Kong–based co-head of Asian economics at HSBC. “That means the reforms in which he is taking on vested interests could fall by the wayside.”

Defying Expectations

Looking relaxed in a traditional barong tagalog -- a translucent lightweight formal shirt -- Aquino said in a May interview in the presidential compound that he can emerge victorious. He has defied expectations before. A bachelor with a weakness for cigarettes and computer games, he spent much of his life in the shadow of his parents, the two most-revered figures in the nation’s struggle for democracy.

His father,

Benigno Aquino Jr. -- nicknamed Ninoy -- was a charismatic opposition leader and senator jailed for eight years by Marcos before being allowed to travel to the U.S. for heart surgery in 1980. On his return to Manila in 1983, Ninoy Aquino was led off the plane by Marcos’s troops and shot dead by soldiers on the tarmac of the airport that now bears his name.

Marcos’s widow, Imelda, said in an interview with Bloomberg Markets in June that neither she nor her husband ordered the assassination.

People Power

However, the killing was the catalyst for a fragmented opposition to unite behind the widowed Corazon, who challenged Marcos and was swept into the presidency in a 1986 People Power uprising. The devoutly Catholic former housewife then withstood at least six coup plots to complete her full term and hand over power to an elected successor,

Fidel Ramos.

By contrast, Noynoy had an uninspiring track record in business and politics. After graduating with a bachelor’s degree in economics from Ateneo de Manila University in 1981, he worked in various management positions in the family insurance company, Intra-Strata Assurance Corp., and on the Aquinos’ 6,400-hectare (15,800-acre) sugar plantation, Hacienda Luisita.

In 1998, standing for the centrist Liberal Party, he was elected to the House of Representatives and served there for nine years before voters sent him to the Senate in 2007.

Aquino wasn’t even originally supposed to be the Liberal candidate in the last presidential election. The chosen contender was

Mar Roxas, a graduate of the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania and a former investment banker at New York–based Allen & Co.

‘Definitely Surprised’

Then, in August 2009, nine months before the poll, the revered Corazon Aquino died, sparking a wave of emotion among Filipinos, 300,000 of whom turned out for her funeral. Petitions circulated urging her son to run for president, and a month later Roxas stood down in favor of Aquino, who won the presidency by more than 5 million votes.

Filipinos were lucky that Aquino rose to the challenge, says

Edwin Gutierrez, a London-based Filipino-American portfolio manager with Aberdeen Asset Management Plc.

“He’s definitely surprised on the upside,” says Gutierrez, who helps manage $10 billion in emerging-markets debt.

Filipinos may not be so fortunate with their next president, given their preference for personality rather than party-driven politics, Gutierrez says.

The Marcos family, for instance, still wields clout.

Ferdinand Marcos Jr., 56, the dictator’s son, won a Senate seat in May and confirmed in an interview that he is considering a bid for the presidency.

Aquino brushes aside fears about who will succeed him.

“I didn’t have any ambition to be president,” he says. “It was fate. The people found me. I am sure they will be able to find another one out of 95 million.”

Leaving the choice to fate sounds risky in a country that has been so let down by leaders in the past. If Aquino is to make the most of his second life, he may have to play an active role in persuading Filipinos to elect someone who can build on his legacy.