The Philippine flag is raised in this famed Paris museum—all because of our anting-antings

The playwright and curator Floy Quintos has exposed part of our secret soul in the City of Light. At the Musée du Quai Branly along the banks of the Seine, the exposition he put together explores the story of our amulets and the complex, hybrid nature of the Filipino faith .

Renee Ultado | Mar 16 2019

ABS-CBN News

|

|

The Philippine Flag stenciled with sacred symbols and incantations, flanked by Dino Dimar photographs of current cult members wearing their anting-antings.

|

It was a windy Monday morning when the Musee du Quai Branly opened its doors to the press, collaborators, friends, and select patrons for the opening of two exhibitions for Spring. The buzzy Oceania assembles almost 200 archaeological objects and art pieces representative of the Pacific island cultures, while Anting-Anting—to which I was invited—is a more intimate installation telling the story of the historical and contemporary use of protective amulets, talismans, and charms in the Philippines.

This feels like coming home, " I said, soliciting a genuine noddy smile from a docent as she ushered me into the exhibit space, an obscure area floating above the museum's permanent collection. It was a half-lie. Whie Santo Niño, the Nazareno handkerchiefs and the odd bits of brass jewelry looked familiar, the whole ensemble felt very foreign to me. Eerie and ominous. A physical manifestation of things I have only heard before.

The exposition entitled Anting-Anting: The Secret Soul of Filipinos explores and demystifies these “charged objects” utilized by a myriad of Filipinos to this very day, from policemen to cult members. An offshoot from a previous exhibit at the Yuchengco Museum in Manila, the collection was built and curated by playwright, director, and antique dealer Floy Quintos.

|

|

Images of Jesus Christ and the Santo Niño figure into these ancient amulets in brass and ivory, highlighting the Catholic influence on the animist nature of the anting-anting.

|

The invitation to show here in Paris came with challenges, mostly reworking the storytelling for a predominantly European audience. “My French colleagues would ask me, okay, how do the objects talk to me? How do we make them engage?” Quintos shares. He had to make the exhibit relatable and transportative even to people who have never been to our islands.

And transportative it was. Utilizing the Atelier Martine Aublet, a space designed to be a “contemporary cabinet of curiosities,” Quintos repackaged the exhibit into smaller pockets of stories. One corner shows Rizalista cult paraphernalia, another reveals blood-stained linen vests with pearl buttons believed to bestow protection against bullets.

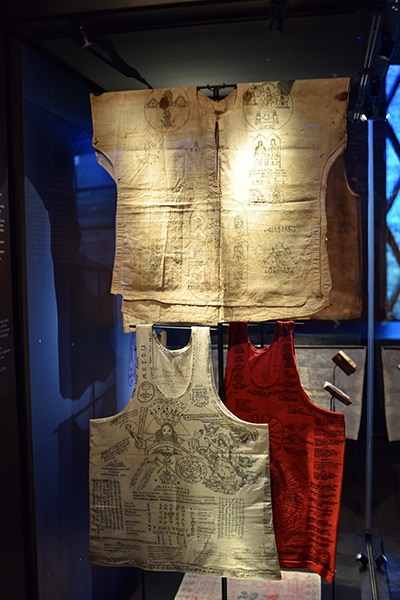

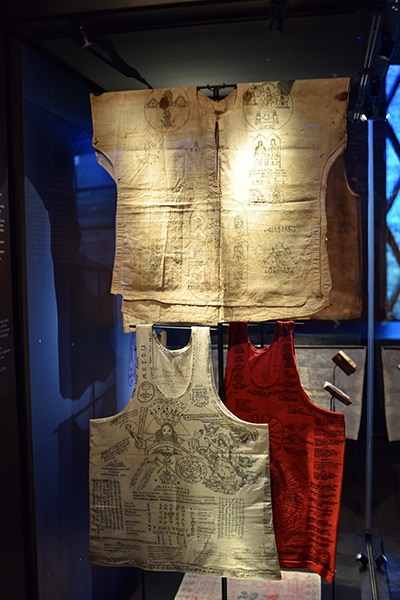

In 1967, socio-political cult Lapiang Malaya marched into Malacañang, equipped only with bolos, anting-anting, and these stenciled shirts believed to make the wearer invincible against bullets. In 1967, socio-political cult Lapiang Malaya marched into Malacañang, equipped only with bolos, anting-anting, and these stenciled shirts believed to make the wearer invincible against bullets.

|

|

On the other side, a wall glows with images from a Dino Dimar documentary following the journey of pilgrims to Mount Banahaw. The space is then infused with noises both familiar (the hypnotizing sound of a waterfall hitting the plunge, a solemn rendition of Ama Namin) and unfamiliar (orations in Pig Latin murmured from sacred booklets). One is given the impression of being in the caverns with the faithful as they pray, light candles, slither into crevices, and collect blessed water.

|

|

Quintos photographed outside the Musée du Quai Branly in Paris. “My French colleagues would ask me, Okay, how do the objects talk to me? How do we make them engage?” Photographs by Claudio Fleitas.

|

Some bearing iconographies from the Catholic religion, the anting-anting is one of the many portraits of Hispano-Filipino postcolonial hybridity. Did the Spanish try to make their Gospel more relatable, and the process of evangelization smoother, by incorporating bits and pieces from the native religion? Or did the Filipinos feign allegiance to the Catholic faith while discreetly continuing their animistic ritual under the nose of the colonizer? “That’s the question. It was the kind of dialogue we wanted to highlight,” says Quintos.

|

|

The hi'wong is an Ifugao shaman's amulet functioning as a portable idol (1) while the Lingolingo, also from the Ifugao, is a golden pendant worn to ensure good health, fertility, safety, and bounty. Towering over a collection of commercially-produced amulets (3), it shows the potent pre-colonial origins of the anting-anting and its still-widespread use in contemporary society.

|

A special nook stripped of protective glass is transformed into a tienda of modern anting-anting, open for people to look closely and even touch. Here, they are less spiritual and somehow devoid of a deeper meaning. Quintos wanted to show how they are today more recognized as popular charms, tailored to augment the spirit or help fix daily woes. It is truly revelatory of the multiple ways we practice our faith in the present. I think of my mother, probably the most Catholic person I know, who keeps her Vatican rosaries next to a Buddha sculpture, or my peers who hear mass on Sundays but wander around with a rose quartz crystal in their coat pocket the rest of the week.

|

|

The Philippine flag stenciled with sacred symbols and incantation

|

The show ends in a juxtaposition of cheap, commercially-made trinkets stacked in a pile under an ancient portable idol carved from stone by the Ifugaos. It shows that the need to always carry a tangible piece of the divine, be it for protection or for luck, is universal and distinctly Filipino. It transcends class, languages, and cultures, and reminds us that everyone, from lovestruck tweens to jittery dispatched soldiers, could use a little help from beyond.

Photographs by Claudio Fleitas

The exhibit Anting-Anting : L'Âme secrète des Philippins runs from March 12 to May 26, 2019 at the Musée du Quai Branly - Jacques Chirac 37 Quai Branly, 75007 Paris, France